Traumatised and alone – why are we still sending survivors of abuse to detention centres?

Metro Exclusive,

Sunday 7 Nov 2021 8:00 am

Following years of violence at the hands of her husband, in 2002, Gloria Peters fled her home country of Kenya.

It had been a difficult decision to make, and one that saw the mum-of-one leave her son with her sister, in a bid to protect him from the uncertainties and dangers of travel.

As Gloria nervously boarded a plane to the UK, she held onto the hope that it would take her to a place of safety and security. She saw it as a place where she could start a new life, free from fear of her partner, and somewhere she would eventually be reunited with her son.

Instead, what followed was years of uncertainty, dread and fear – and even a spell at the infamous Yarl’s Wood detention centre.

‘When you’re desperate, you do what you need to,’ remembers Gloria. Explaining how she came to the country on a visitor visa, she says. ‘It meant I wasn’t allowed to work, so had to rely on handouts from friends as a temporary measure. But I couldn’t continue to live like that so eventually started working informally as a cleaner.’

For two years she worked for cash cleaning homes, but as time went by Gloria began to realise the precarious situation she was in. Friends would tell her to be careful, warning that she could be picked up at any time and deported as an overstayer.

‘I didn’t even know what deported meant,’ she admits. ‘But when I found out, I didn’t want it to happen to me. I’d think about all that I had fled from – and the fear of my husband instilled in me.

‘Many women like me flee our home countries because we cannot get protection from the authorities when we suffer rape, domestic abuse, and other forms of sexual violence,’ Gloria goes on.

‘We are never told that these are grounds for asylum and even our own lawyers and people we seek help or advice from don’t tell us – we are left in the dark.’

Gloria, now in her fifties, ended up being detained for two months at Yarl’s Wood in Bedfordshire, a detention centre that has been blighted by controversy and criticism since it opened two decades ago, in November 2001.

Although originally meant to hold 900 people, a fire started by detainees just three months after it opened, meant that the centre has never operated at full capacity.

Instead the building holds around 400 people, with the vast majority, until recently, being women – many of them vulnerable, having escaped from violent and sexually abusive pasts.

In a 2015 report published by Women Against Rape and Black Women’s Rape Action Project, hundreds of former detainees revealed their stories of sexual abuse and mistreatment at Yarl’s Wood

Allegations of inappropriate sexual activity by staff and abuse have long rocked the centre for years, while in a 2015 report published by Women Against Rape and Black Women’s Rape Action Project, hundreds of former detainees revealed their stories of sexual abuse and mistreatment there.

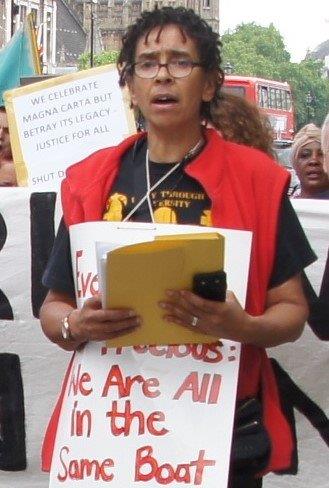

In its conclusion, the report called for Yarl’s Wood to be closed and was followed by protest of 200 women calling for action in response to the harrowing stories.

Although in August 2020 the centre finally ceased to hold women, the Home Office has since announced plans to open a new one for women in County Durham – a huge blow for those who have been campaigning against the use of detention for women.

‘When we started campaigning in 2014, there were about 300 women in detention,’ says Gemma Lousley of Women for Refugee Women. ‘By the end of March 2018, the figure had fallen to 121 women. Since the pandemic, recent statistics show that by the end of June 2021, there were 37 women in detention.’

Many campaigners believe that with the number of women in detention being so low, this would be the ideal time to end their use altogether.

‘The abolition of women’s detention is very much an immediate possibility,’ adds Gemma. ‘The Home Office’s decision to open a new detention centre for women, when the numbers of women in detention are currently so low, is utterly illogical.’

Before she was detained, Gloria says that her life was an endless balance of trying to get by without being noticed by the authorities, while working with lawyers, who she believed would help her remain legally in the country.

One solicitor, who she was introduced to in 2004 by a friend, charged her over £4,000 to put in leave to remain paperwork, while another later cost £6,000.

Meanwhile, the Home Office also caught up with Gloria, warning her on several occasions that she was subject for removal from the country as she had overstayed her visa.

‘The whole process drains you all of your energy,’ Gloria says.

For nearly 18 years she managed to stay in the UK, but when she went to sign on one day in 2019, her world came crashing down.

‘I was taken straight to the detention centre,’ remembers Gloria. ‘Everything felt in slow motion, like someone taking over my life. I couldn’t believe it was happening.’

As Gloria grappled with the trauma of being imprisoned and facing a terrorising journey back to the abuse she had fled, she also discovered that her autonomy would be taken away in detention.

‘Your freedom is stolen, and you have no choice about the things you can and can’t do,’ she says, adding that the women would have to gather for meals in a communal dining room three times a day and were not allowed to take their food outside that room.

‘None of the meals have any nutritional value,’ Gloria says disdainfully.

‘It wasn’t suitable for anything moving, even animals. I am very health conscious and it affected me knowing that all the food I was eating was junk with no nutrition. The fruit was overripe and often inedible. Everything was overboiled, too salty, too spicy, or too oily. But when you have no choice, you just have to get on with it.’

I was locked up in a prison, even though I hadn’t committed a crime

The sleeping arrangements were no better, she recalls, describing how the rooms held two beds, a toilet, a small window that couldn’t be fully opened, and a shower.

‘The mattresses we slept on were like cardboard. It wasn’t even a single-sized bed. If you’re not careful, the water from the shower will flow into the rest of the bedroom,’ Gloria explains. ‘At night, it was very noisy – women couldn’t sleep and would be talking through the night. Because the walls were so thin, you could hear every conversation. The guards would come in the rooms – with their noisy keys and stomping boots – and put on the lights to check if someone is in or gone.’

When she started to experience a familiar burning sensation in her feet and legs, one that she had suffered from for years, Gloria reported her pain to the guards, only to be told that they could not give her medicine other than paracetamol. ‘The pain was so bad I felt like I was going to pass out and die,’ she recalls. ‘Still they only gave me paracetamol. I had to swallow it with them standing there, watching me. I couldn’t take it to my room.’

Gloria tells how she would spend her days going through the motions of mealtimes and checking emails, while dealing with the fear of being forced to return to a life of abuse.

‘During the time I was there, I never went out for fresh air,’ she says. ‘I didn’t see the point of sitting in the one small space for two minutes of fresh air. I was too stressed out.

‘You’re sitting around, not doing anything. Everything I had forgotten from the past came back to me – like it was all happening again. It was very hard. But there was nowhere to run. I was locked up in a prison, even though I hadn’t committed a crime. It was horrible.’

Eventually Gloria contacted Women Against Deportations, a coalition of charities and activists who co-ordinate anti-deportation work, who gave her a self-help guide, which offered advice on how to get out of detention and claim asylum.

After two months of beng detained she manage to secure her release. However, her fight still isn’t over as Gloria’s case is ongoing and she continues to live in limbo, waiting for the day her request for asylum is granted.

Despite living in the UK for nearly two decades now, the emotional scars of what she has been through are still very raw – when asked about the young son she left behind, Gloria still can’t bring herself to talk about him.

Cristel Amiss works for Women Against Deportations and says that she believes the purpose of detention is ‘to punish, isolate and make it as hard as possible for people to pursue their legitimate claim’.

She adds that she’s heard of instances where their self-help guides were intercepted, confiscated, and even stolen by staff, all illegal actions that were later highlighted in media coverage.

‘There were many difficulties speaking to women on the phone – going through the switchboard was impossible as no one would answer.’

Speaking about how some women deal with such loss of control and rights, Cristel says they have been forced to protest through with sit-ins and hunger strikes.

Remembering one woman she supported, Cristel tells how she resisted being deported by refusing to dress. ‘The guards dragged her naked through the wing as women tried to stop her being taken,’ she says. ‘The staff were furious and put her in the punishment/segregation wing. Following a fresh claim, she was freed, and just this year, finally won full refugee status.’

‘Nobody was there except the guard who searched me and took everything I had,’ she adds. ‘The next morning, I had an induction to show me where things were at and tell me all the rules.’

Although now 62, Bibi can still remember the experience clearly. ‘Everything at detention was horrible,’ she recalls. ‘The food was the worst you could ever have. The detainees would often cook it. Even if you don’t want to eat it, they force you to. And the healthcare – the nurses were so rude. I developed a lot of anxiety and depression – one time, my blood pressure was so bad they had to take me to the hospital. They put handcuffs on me to take me.’

As Bibi could speak English, she supported the many other women in the centre who didn’t. She remembers talking to petrified women who had been sexually abused by guards, some of them who became pregnant.

‘I was always having problems with the guards because I helped to introduce women to people that could help them, who could access lawyers and interpreters,’ says Bibi. ‘The guards didn’t like that I spoke up for women.’

Bibi spent a total of nine months in detention at Yarl’s Wood. ‘It was such a horrible place to be – inhumane the way people treated us like a piece of s**t – like we had no rights,’ she recalls.

Eventually, with the help of the All African Women’s Group, Bibi was released from detention, and was finally granted asylum nearly 20 years after she arrived in the UK. She now supports women in detention centres.

However, as with many women who have been detained at Yarl’s Wood, having experience such severe trauma caused Bibi to suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Now, as she lives in the UK as legitimate citizen, she confesses she can hardly bear to think about the nine months in what felt like prison.

‘I don’t want to remember it,’ admits Bibi. ‘I don’t want it to backlash on my mind.’

Adetola* sat in her room at Yarl’s Wood for six months in 2019, only leaving to eat breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

‘They tried to make us comfortable by having a gym, a little garden, and activities to do – to make us feel like we weren’t locked up,’ she remembers. ‘But I was never comfortable.’

Adetola, who came to the UK from Nigeria, had been exploited and trafficked prior to her entrance into Yarl’s Wood in 2019.

‘I was already depressed before I went in,’ she says tearfully, explaining that after months of sitting with her memories and fears, her mental health worsened. ‘I felt like I was better off dying. I could have killed myself, but they prevent things like that.’

To fight her case, Adetola, 38, hired a private lawyer. ‘But he just took advantage of me – took my money and did nothing.’

Eventually, she found a trustworthy solicitor through the Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants, who managed to secure her release from detention, and win her asylum case.

‘The problem with the current system is that survivors of trauma, abuse and exploitation are being treated as immigration offenders first, and then victims, which has long term consequences on them,’ says solicitor Shalina Patel.

Solicitor Shalina Patel says that a number of her clients seeking asylum have received inadequate legal advice in the past

She explains that although detention centres are required to have a legal aid advice rota where different firms come in and provide advice, the system changed a few years back and the contract was given to numerous firms without adequate checks having been done.

‘I would say a high percentage of my clients have been provided inadequate advice and for that reason they have remained in detention for longer than necessary or even had their claims refused,’ adds Shalina, who works for the trusted firm, Duncan Lewis Solicitors.

When Voke* started to hear voices in her head during her eight-month stay at Yarl’s Wood in 2017, she went to the doctor on site to request treatment.

‘They said they didn’t think I needed any medication – that I was fit to travel, good to go,’ she remembers.

On another occasion, Voke – who had been trafficked to the UK from West Africa – remembers experiencing severe abdominal pain. ‘They didn’t give me anything for it,’ she says. ‘I didn’t have my period for the entire eight months.

‘My body had just shut down – mentally and physically. When I think about those days, I cry,’ adds Voke, who is in her forties. ‘They treated me like I was nobody. They just want to ship you out, like cargo.’

Emma Ginn, Director of Medical Justice, has voluntarily visited women in Yarl’s Wood since it opened in 2001, documenting their scars of torture and any serious medical conditions so that they can be properly considered in their immigration and asylum cases.

‘Healthcare in immigration detention is inadequate,’ she says. ‘Detention in and of itself can exacerbate existing medical conditions and be the cause of mental illness. Some women have deteriorated to the extent that they have lost mental capacity and some have been transferred back and forth between secure psychiatric units and Yarl’s Wood.

‘Hunger-strikes are not uncommon,’ adds Emma. ‘Self-harm rates are high and some women have been handcuffed and held in segregation as a result.’

Meanwhile, Gemma Lousley from Women for Refugee Women adds, ‘The majority of women in detention are survivors of gendered violence and racially minoritised.

‘Instead of offering them safety and support, they are punished and traumatised by immigration enforcement practices like detention.

‘Rather than give help, the Home Office locks them up.’

A Home Office spokesperson told Metro.co.uk: ‘The public rightly expect us to maintain a firm and fair immigration system, which detention plays a crucial role in enabling the removal of individuals who include serious, violent and persistent foreign national offenders. It is vital that detention and removal are carried out with dignity and respect. That is why we take the welfare and safety of people in our care very seriously and accept nothing but the highest standards from service providers that manage the detention estate and the escorting process.’

Source:

Traumatised and alone – why are we still sending survivors of abuse to detention centres?